Hello everyone, and welcome to a new issue of Words for Worlds - the Book Issue (at last!).

Yes, we ironed out the final details, and here it is: my third novel, THE SENTENCE, releasing formally on 21 October. Pre-orders, however, are open, and you can pre-order here (and if you don’t want to pre-order from the Big A, Champaca Books also has a pre-order option). If you’re someone who intends to read this novel at some point, may I request you to consider pre-ordering: it signals early interest in the book, which tends to have a spill-over effect as its life commences.

There is also a Goodreads page for the novel (here).

If you’re outside India, these links may not work, because as of now, this novel is only published in South Asia (more on that below). But if you do want to read, drop me a mail, and we’ll try and get you a review copy.

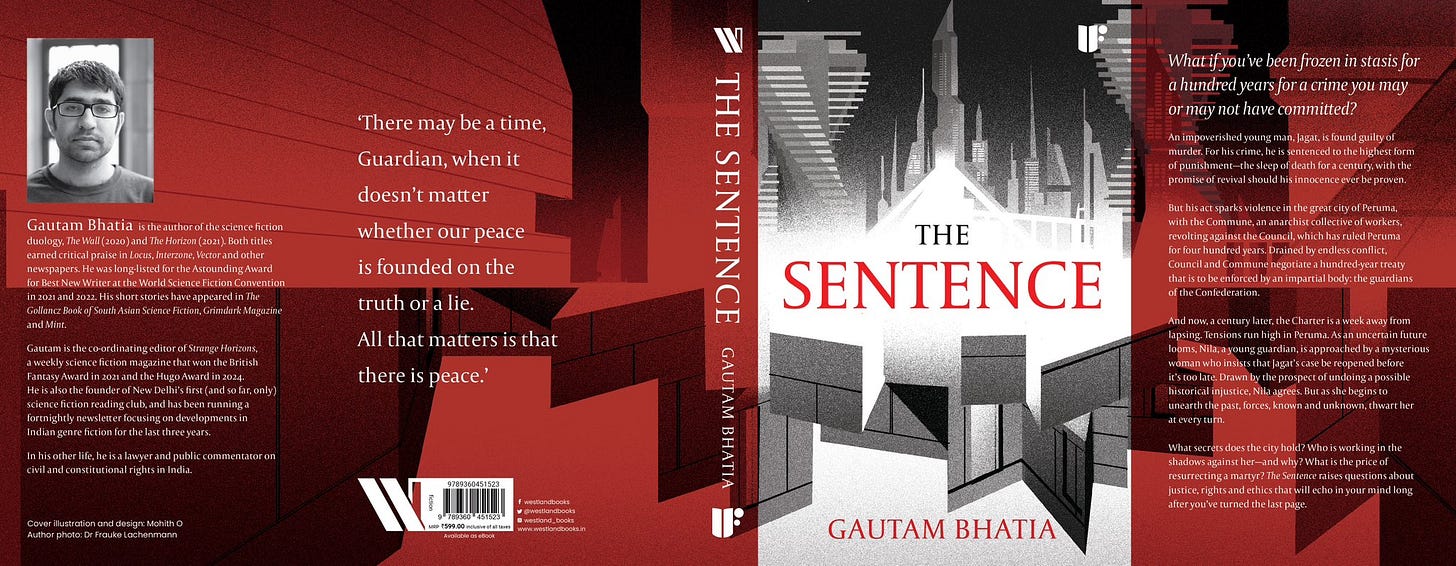

Here is the full cover spread. And here is the blurb:

What if you’ve been frozen in stasis for a hundred years for a crime you may or may not have committed?

An impoverished young man, Jagat, is found guilty of murder. For his crime, he is sentenced to the highest form of punishment—the sleep of death for a century, with the promise of revival should his innocence ever be proven.

But his act sparks a bloody conflict in the great city of Peruma, with the Commune, an anarchist collective of workers, revolting against the Council, which has ruled Peruma for four hundred years. Drained by a war without end, Council and Commune negotiate a hundred-year treaty that is to be enforced by an impartial body: the guardians of the Confederation.

And now, a century later, the Charter is a week away from lapsing. Tensions run high in Peruma. As an uncertain future looms, Nila, a young guardian, is approached by a mysterious woman who insists that Jagat’s case be reopened before it’s too late. Drawn by the prospect of undoing a possible historical injustice at a fraught time, Nila agrees. But as she begins to unearth the past, forces, known and unknown, thwart her at every turn.

What secrets does the city hold? Who is working in the shadows against her—and why? What is the price of resurrecting a martyr? The Sentence raises questions of justice, rights and ethics that will echo in your mind long after you’ve turned the last page.

There is SF here, there is a smidgen of crime, and of course, there are ideas from my “other life” as a lawyer. One of the things I did want to explore in this novel was anarchism through the lens of SF, and so there’s a fair bit of that as well. The Paris Commune (among others) is a major historical inspiration for this novel. There are, of course, a lot of little asides and insider references to contemporary India. As for the rest - I hope to talk about it in due course, once the novel is out into the world, and people have a chance to engage with it.

I want to talk a little bit about the history of how this novel came into being, especially for folks finding their way around these processes (especially the publishing process).

I began writing it at the summer of 2021, soon after I’d finished The Horizon, and completed my Sumer duology. It began life as the kernel of an idea, as a 15,000-word novelette that expanded into a 45,000-word novella, and finally into a novel. With beta reads and feedback, I had a finished draft ready by March 2023 - so, a writing period of around 21 months.

My prior experience with publishing SF in India meant that - unlike the last time - I began with querying US and UK agents, instead of looking for an Indian publisher. As with The Wall, it was an exercise in futility: non-responses, ghosting, and form rejects (some of them quite humiliating). I’ll probably discuss the causes behind this in another newsletter, but for now I just want to flag this, as I know that it’s something a lot of other people go through as well. I also want to say that this is an immensely frustrating experience, and that it’s legitimate to feel angry about the way this process is structured, with its stacked deck and its patronage structures. This is especially so because social media is full of people who subliminally hammer in a message that one should be “resilient” and “persist”, until one finds an agent who will “fall in love” with your book, and “champion” it (what is this, a medieval duel?). This is all American neoliberal corporate-speak, so once again - if the process is angering you, it’s because it should anger you. But more on that in another newsletter.

With The Wall, I had persisted for around a year and a half, through around 75 queries. This time, at around 50 failed queries and the six-month mark, I stopped. The thing about writing agent-tailored queries is that it is an exhausting process, and at some point, you find that the time you could be spending on actually writing and working on your craft, you’re spending formatting query letters. I sensed time just draining away as I broke my brain drafting query letters while I could have been writing, so I decided to suspend the process and go down the India route once again.

I approached a few publishers. One of them was Karthika VK of Westland. Westland might not ordinarily have been on my radar for SF, but for two things: Karthika had come to some of the early meetings of our Delhi Science Fiction Reading Circle, and she had recently acquired Gigi Ganguly’s collection of short SF, Biopeculiar (incidentally, also in some manner via the Reading Circle). This signalled to me an active interest in SF. And then of course, Karthika’s reputation as an editor was impeccable (only, I’d never previously associated her with SF).

I pitched the book to her at the end of October 2023, and even though I’d pitched it elsewhere and was waiting for offers, after our first meeting, I knew this was it: before even making an offer, Karthika had read the manuscript, and had detailed editorial suggestions - suggestions that identified the weak parts of the draft that I had intuited for myself, and offered fixes that I immediately sensed were right. We wrangled a bit over email about contract details (inevitable!), and I signed soon after.

My experience with Westland over the last few months has been nothing short of brilliant. The manuscript went through two rounds of comprehensive substantive external editing with Karthika and her colleague Ajitha (I know this sounds like a baseline, but you’d be surprised at how often it just doesn’t happen), and then two rounds of line-editing with another colleague, Sanjana, where we hammered out further substantive details. With each round, I felt the manuscript (and my own craft) improving; some of the changes I was asked to make were challenging, but it didn’t take me long to see the sense behind them (even when I didn’t entirely agree). At each step, the process was entirely collaborative: a collaboration that then extended into jointly devising a marketing plan (too often, these are templates that are imposed upon authors), and jointly iterating over a cover (the final version is what you now see before you).

In the course of this process, I also came to learn a lot more about Westland, the publishing house. It is a trite thing to say that publishing is embedded in capitalism, and publishing houses therefore have no choice but to follow the money, often publishing work with dubious literary merit, or - worse - work that is politically harmful (especially in non-fiction). Watching the books that Westland has put out over the last few months, however, has been nothing short of inspiring: from books about political prisoners to memoirs of the 2002 Gujarat riots and beyond, these are books that other publishers won’t touch (and - apparently - have not touched, despite being invited to do so).

What’s more inspiring is that many of these books were clearly commissioned before the results of the 2024 General Election. I don’t need to explain why that is even more admirable.

Westland’s commitment to courageous, progressive political non-fiction is matched by its commitment to taking risks in the domain of fiction. I’ve already mentioned Gigi Ganguly’s collection; apart from this, a few months ago, in the books section of a Bombay hotel, I came across a mammoth, 1000-page novel set in the north-east (I’ve unfortunately forgotten the name). As I flipped the pages, I was wondering which publisher had taken such a commercial risk on such a tome, and then I came to the acknowledgments thanking Karthika and Ajitha. Of course.

Westland’s willingness to stick its neck out in multiple ways extends to genre as well. Gigi Ganguly’s book was the first in a new SF imprint called IF (I was party to some of the initial discussions around the imprint’s name and design). Soon after that, a Rivers Solomon reprint was #2, and The Sentence is #3. As Indian SF writers, one thing we often complain is the lack of infrastructure supporting Indian SF, a crucial part of which is dedicated SF imprints. Well, IF now exists - and I think it’s once again worth stressing on the commercial courage needed to create a whole imprint for a genre where many people would question whether a reading public exists in the first place!

All of which is to say that in a publishing industry that actively encourages cynicism and jadedness within all who participate in it, and which constantly subordinates creative impulse to the dictates of an imagined and constructed “market”, working with Westland has been a dream.

I brought up the history of The Sentence above because, after all that I’ve said about Westland, I did not also want to give a wrong impression that I sought them out from altruistic motives right from the beginning. As I wrote above, I tried querying abroad, failed, and then tried the India route. But there is a reason why all of us Indian SF writers query US/UK agents and publishers (some of us more successfully than others), even as the result of that is often performing “Indianness” for a western audience. The centre of publishing power is still the US/UK, and while books easily flow from the global North to the global South, they do not flow at all the other way: books ignored as long as they’re published in India are suddenly showered with attention once they have a US/UK publisher. These are problems that are structural, and problems that Westland cannot solve on its own, and as long as these problems exist, publishing Indian SF in India will continue to be bedevilled by these issues.

So, my publishing The Sentence with Westland had an element of contingency, but it’s a contingency I’m very glad for because now, looking back on it all, I would not have it any other way. Ultimately, this is an Indian SF novel, written by an Indian, and shaped in an Indian context - even though its draws its inspirations from a global, radical and anarchist history. And in that Indian context, I could not imagine finding a better, more principled publisher than Westland - both when it comes to the politics of the publishing house, and in its approach to genre.

Which is why I’ll close by saying: if you’re an unpublished Indian SF writer who’s read this far, and are wondering how to “break into” a scene that presents an increasingly opaque and forbidding face to new writers, consider Westland and consider IF. There are problems of power and resources in global publishing that we’re not going to be solving anytime soon, but you couldn’t find a better set of people to handle your words with the care and the generosity that they deserve.

So yes, The Sentence is now (almost) out in the world, and if you’re a reader of this newsletter who plans on getting it, I’d love to hear what you think, whenever you’ve read it. As a reminder: the pre-order link is here; and if you’re inclined to check out the back-list, here are the links to The Wall and The Horizon.

This is so encouraging to hear, wrt Westland. So glad they exist. And yes, I'm here for a post about how frustrating and asymmetrical the querying process is. As you well know.

Congratulations! And, thank you for taking us through the process from conception to (almost) release - interesting, if depressingly grim in parts, as publishing so often is. I'm glad The Sentence found a welcoming home in Westland.