Hello everyone, and welcome to another issue of Words for Worlds.

I came back from a fortnight of travel this morning to the first advance copies of THE SENTENCE on my desk.

This is the first time I’ve seen the physical copies of the books (it’s a feeling that never gets old). The novel formally releases in exactly two weeks (on October 28), and in the meantime, you can pre-order it here (a general reminder that pre-orders help authors!). And if you don’t want to use the Big A, there’s Champaca and Midland to order from, and you’d be helping your local independent bookshop as well. Incidentally, if you’re living outside India and are interested in the book, it turns out that Midland delivers abroad, so take a look and see if you can order from them!

My travels this month took me to Glasgow, which also meant that I could pick up one of the Hugo trophies won by Strange Horizons at WorldCon this year. The trophy had to go through five airports in check-in baggage (Glasgow, Heathrow, Luxembourg, Istanbul, Delhi), and I was convinced that I would pull it out of my suitcase at home, broken into many pieces. It appears, however, to have made it safe and sound.

That is a rather big rocket, if I may say so!

What I’m Reading

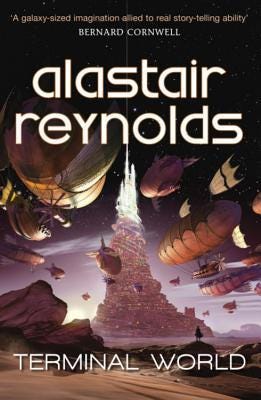

I took advantage of several internet-free flights to make some ground on my ongoing project of reading through Alastair Reynolds’ backlist. First up was Terminal World.

As you’ll probably gauge from the cover, Terminal World is a mash-up of space opera and steampunk (space-steampunk?). The tower city in the middle of your vision is “Spearpoint,” where the book’s action begins. The premise is classic Reynolds: both brilliant and generative. Each level of Spearpoint exists at a different level of technology (from Circuit City up top, where post-human angels fly), down through Neon Heights, Steamville, and the medieval streets of Horsetown at the tower’s base: and these levels of technology are not socially determined, but in some way that nobody knows, a part of the laws of physics that govern this world. And then there’s the wide beyond, as the novel’s protagonists discover when fleeing Spearpoint: a frontier of lawlessness where a collective of airships called the Swarm holds sway.

Most of the action takes place in and around the Swarm, and is steampunk-ish: but there are moments - primarily involving Spearpoint and the history of the world, where the novel’s space opera undercurrent comes to the surface, and the classic Reynolds sense of wonder at the vastness of the universe.

If I didn’t enjoy Terminal World as much as I have some of the other Reynolds novels (such as the Revelation Space series, or House of Suns) it is at least partially because steampunk simply isn’t my thing; but also, in most un-Reynolds-esque fashion, this novel had a lot of deus ex machina when it came to last-moment escapes for the protagonists, and its atavistic descriptions of one group of antagonists (the Skullboys) left an unsatisfactory taste in the mouth. Not my favourite Reynolds, but I did like it, and to fans of steampunk, it’ll certainly have a lot to offer.

And then back to familiar space opera territory, with Bone Silence. I didn’t know quite why I did this, but I read Bone Silence - the final book in the Revenger trilogy - before reading either of its predecessors (well at least I didn’t review it, as some people have been known to do with series!). So a few of the references passed over my head, but only a few: for the most part - and this is testament to Reynolds’ skill - it didn’t really impact my reading pleasure. I did feel, however, that of all things, this book had a pacing problem: by the time I got to the final, breathtaking twist on page 580/600, I was exhausted enough to simply not respond to the extent and depth that the nature of the reveal demanded. Thee was also perhaps a little too much space warfare in this book for me, although it was all expertly depicted, of course.

The strongest part about the novel - as with all of Reynolds - is the premise: thirteen human civilisations that rise and fall over the long millennia, and the curiosity of two space privateers to understand what lies behind that - once again, the ambition of the premise takes your breath away, and despite the mammot 600 pages, does have you reading till the end.

I was one of the minuscule minority of readers that did not like Simon Jimenez’ debut novel, The Vanished Birds. Then, a lot of people whose opinion I trust told me that even if I didn’t like The Vanished Birds, I’d love his second novel, The Spear Cuts Through Water. After having it stare at me in the SFF section of various bookshops in various cities in the world over the last few months, I finally gave in and bought a copy at Toppings at St Andrews earlier this month (gorgeous SFF collection, by the way). And, well…

Alright, let me start with the good things first. Jimenez is a fantastic prose stylist. This was evident in The Vanished Birds, and its even more evident in The Spear Cuts Through Water. At the level of the sentence, this is virtuoso writing.

Then, we also have the concept of the “inverted theatre,” an afterlife-y space where the events of the novel are performed, and non-protagonist participants in those events intervene with their own thoughts and recountings; this is a device I’ve never seen used before in fantasy, and it does expand the perspectives in the novel in interesting ways.

But now to the other side: at the end, I cannot say that I liked The Spear Cuts Through Water, because for me, it embodies a particularly reactionary strain of politics that has come to define a lot of modern SFF, a reactionary strain that is more insidious because it is cloaked in progressive form. This often plays out in the following manner: the antagonist is an evil Empire, which regularly enacts spectacular and gruesome violence upon dissidents, as well upon its own subjects. Then there arises a challenge to this Empire - not through a popular movement or a rebellion, but through a disgruntled or betrayed royal, who often joins forces with a token commoner, and together they take down the Empire: again, not with a view to destroying imperial rule as a form of social and political organisation, but with a view to restoring the right kind of rule. And they will do so by enacting their own methods of violence. In the crossfire between the two sets of combatants, the People (whoever they serve) are cannon fodder: they die frequently, they die in numbers, and we rarely, if ever, see them as bearers of political and social agency.

You’re probably thinking “he’s just described the Lord of the Rings” - and a discussion of the politics of The Lord of the Rings would lead us far afield - but I think it should be evident why what I have described could be fairly labeled “reactionary.” And that is the core structure of The Spear Cuts Through Water.

A word, also, about violence. I don’t think, of course, that fantasy readers can have a general complaint about violence in fantasy novels: unless you’re reading cozy fantasy, overt violence comes with the territory. However, there is something about how large scale, gruesome massacres are baked into the world-building of The Spear Cuts Through Water that just did not sit right with me. I think that, one year into the genocide on Palestine, as SFF writers, we should be thinking more seriously about world-building choices when it comes to treating mass violence as a necessary or unremarkable feature of our worlds (as The Spear Cuts Through Water does). Indeed, in The Spear Cuts Through Water, one of the protagonists is a repentant member of the royalty who has committed mass murder in its name, and is now traumatised by what he has done. I’m sorry, but I just do not have any residual patience for the trope of the PTSD-suffering US Vietnam veteran or the Goa-hopping ex-IDF soldier, whether these tropes occur in real life, in war movies, or in fantasy novels.

The violence is not only large-scale, but it is often utterly arbitrary and turned inwards, and this is something that always annoys me when I come across it in fantasy. I’ve called it the “Darth Vader Syndrome” elsewhere: it’s basically the main evil guy arbitrarily and randomly killing his own subordinates. It annoys me because I think it paints the antagonists as incompetent and stupid: your subordinates - including the competent ones - will have absolutely no reason to serve you if you’re going to just kill them off at any time, and the only way to square the circle is a situation where you literally rule by force alone. But that’s never how actual empires have functioned: you can’t rule by force alone. At some level, you have to have buy-in, co-option, hegemony - all of which is impossible if you’re suffering from the Darth Vader Syndrome. A halfway-competent Emperor - even a villainous one - should be able to grasp this basic fact - but not, it seems, the villains of The Spear Cuts Through Water.

I’ll end by noting, of course, that readers have different expectations from fantasy, and your enjoyment of a book is naturally informed by those expectations. I am always on the lookout for the political frames that a novel is directly or indirectly pushing, but that is by no means a prescription about how novels should be read. If you like your fantasy in the Guy Gavriel Kay-style of crystalline prose and atmospheric battles, The Spear Cuts Through Water could well be your thing - it just wasn’t mine.

What’s Happening at Strange Horizons

Since I didn’t have a standard newsletter issue the last time around, I want to take this opportunity to share Shrinidhi Narasimhan’s excellent essay on traditions of non-Anglophone SFF in South Asia: In Other Wor(l)ds. It was a particular pleasure for me to commission and edit this piece; I learnt a lot from it, and I hope you will too.

The Indian Scene

Congratulations to Indrapramit Das for winning the British Fantasy Award for his novella, The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar.

In the new edition of Kaleidotrope, Chaitanya Murali has a short story called “Of Black Town’s Monster.” Give it a read!

Recommendations Corner

I bought The Third Love purely on the strength of the blurb, and I do not regret it: this is one of the best novels I’ve read all year. First things first: it has not been marketed as a speculative fiction novel, and the industry does not classify it as such, but much like - say - The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, the heart and soul of the story is SF, whatever the label might be. Trapped in an unfulfilled marriage, Riko learns how to travel back in time in her dreams, first to the 17th-century Edo period, and then to the medieval Heian period. In these dream-worlds, she meets Mr. Takaoka - an old friend, and the one who has taught her this form of dream-travel - in different guises; and together, they re-enact doomed love stories that are at the borders of myth and history.

I found The Third Love brilliant both in setting and in execution: the setting echoes, of course, familiar themes of time-travel romances, and the writing alternates between adventure, pathos, wisdom, and humour; some of the descriptions of a noblewoman’s life and loves in Heian-era Japan, in particular, were absolutely haunting. This is one book from my recent reading that I’d unreservedly recommend.