Hello everyone, and welcome to another issue of the Words for Worlds newsletter.

In the 23 June issue of Strange Horizons, I have a review essay on the 2025 Arthur C. Clarke Award shortlist (here). The Clarke is the SF award that I follow most closely (it always throws up at least a couple of books I haven’t heard about, let alone read), and this is the fourth occasion (since 2017) that I’ve written this essay, looking at the shortlist as a whole. In these essays, I try to look for patterns between the shortlisted books (and what that says about the “state of the genre” in general); this year, I found the idea of “retro-renewal” (yes, I made up that term for the purposes of the essay!) a generative one to think through two books about robots, three books about the end of the world, and one book about robots at the end of the world. For more, take a look at the essay!

My personal favourite on the shortlist was Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time, which I thought was a delightful romance with a well-crafted time-travel premise as a backdrop, and by some distance the most accomplished novel on the shortlist. It did not win.

Finally, I’m still waiting to be able to share some publishing news about THE SENTENCE, but in the meantime, as always, you can get the book here.

What I’m Reading

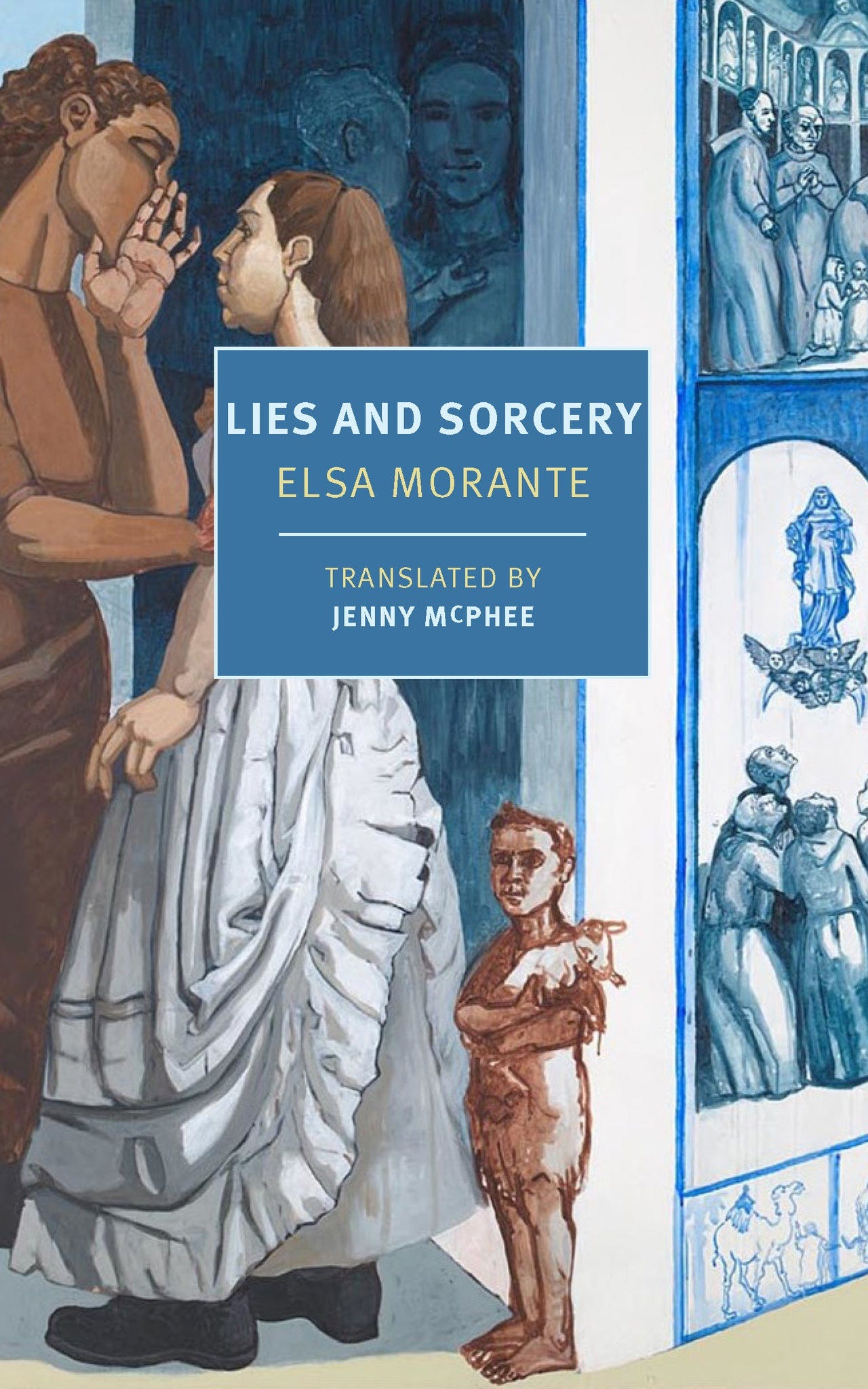

Elsa Morante’s Lies and Sorcery was pitched to me as a rawer, more intense version of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet, so naturally, I had to read the book at once (Ferrante herself is on record with her debt to Morante). Lies and Sorcery is the story of three generations of women (the narrator’s grandmother, her mother, and herself), and the men and women in their orbit. Chronologically, it takes place from the late nineteenth century to the mid twentieth (so, interestingly, it ends around the time the events in the Neapolitan Quartet begin).

There are many things going in Lies and Sorcery, but above all else, I’d call it an inverted bildungsroman. On the surface, you can read it as a mosaic novel that intertwines the coming-of-age stories of three women, across three generations. But the moment you go deeper, you realise that it’s a story about how patriarchy deforms and inverts sensibility, emotion, and relationships. One of the things that Lies and Sorcery does particularly well is to demonstrate how the hold of patriarchy mutates over each generation - from the legally imposed inequalities of the late-nineteenth century to the far more insidious, indirect violence of the mid-twentieth - while never losing its death grip on the lives of people.

One of my favourite lines in all the non-fiction I’ve read over the years is a line by Teju Cole, writing on James Baldwin. Cole writes of “the incontestable fundamentals of a person: pleasure, sorrow, love, humor, and grief, and the complexity of the interior landscape that sustains those feelings.” That line was in my mind as I read Lies and Sorcery, because in this book, you see how these “incontestable fundamentals” bend themselves out of shape under patriarchy. Each generation of women experiences the world mediated by patriarchy, and comes to these “incontestable fundamentals” under its distorting influence (whether it is economic, social, or emotional).

The result is an eerie, unsettling novel, where characters say and do things that ostensibly represent human sentiments at their finest (whether it is romantic love, filial devotion, the steadfast loyalty between friends, or the affection of parents for their children), but which - in the essence - are misshapen into something almost opposite of what they are meant to represent. Tokens that lovers keep to remind themselves of each other are turned into literal brands upon the skin; serenading beneath a window is an act of emotional blackmail; declarations of love are declarations of captivity; and in a final, most disturbing act, relationships have become so deformed that a person is driven to invent an entire collection of letters from a lost love, which they write to themselves.

And perhaps the most disconcerting element of Lies and Sorcery is that its characters are not shamming it. You can’t even say that they are lying to themselves or are labouring under false consciousness, because it is not as simple as that. These characters genuinely believe that this life is the life they want, and their happiness when they think they have it is genuine happiness. This, then, is the final triumph of patriarchy: to create a world so internally consistent and so externally attractive, that the people inside it want that world for themselves.

While Lies and Sorcery does end on a mildly redemptive note - leaving just a sliver of possibility that there is a crack in even the most tightly-constructed of worlds - this is an overwhelmingly bleak novel. To come back to what I began this review with - it is a rawer Ferrante, Ferrante with the prose styling stripped off, Ferrante without the liberating potential of a female friendship at its core, Ferrante without the temporary spatial and emotional respite of Ischia. Lies and Sorcery does not let up; if you go in to read it, don an armour of chain mail around your heart. It may not be enough.

What’s Happening at Strange Horizons

At the end of June, we published our special issue on Afrosurrealist SF. This issue has been guest edited by Yvette Lisa Ndlovu and Shingai Njeri Kagunda, and you will find here a collection of stories, poetry, essays, and reviews, dedicated to the theme.

The Afrosurrealist issue is one of our geographic “special issues,” which feature as stretch goals in our annual fund-drives (previously, we’ve done special issues on Palestine, Brazil, South-East Asia, Nigeria, and India, among others). Speaking of which, the Strange Horizons 2026 fund-drive is now in its final week, and we’re just off our base goal. You can donate here (no amount is too small etc etc.)

The Indian Scene

Congratulation to Amal Singh for the publication of his latest story, “A Land Called Folly,” in the July 2025 issue of Clarkesworld magazine. You can read the story here.

Recommendations Corner

This coming Sunday, at the Delhi Science Fiction Reading Circle, we’re discussing Latin American SFF, part of which is the 1950s graphic novel, The Eternaut. This one has quite the amazing story behind it, with the as-yet-unfinished story acquiring a more political tone in the 1960s, and the artist himself being disappeared by the Argentine junta: a reminder, perhaps, that SFF has always been not only political, but with a radical strain that is far too often erased, especially today. Often, to find this radical strain, you have to look outside the Anglosphere and its publishing industry, and this is a good example of this.

What’s the Delhi Science Fiction Reading Circle, if I may ask?

Intrigued by Lies and Sorcery even though you end the review with 'it might not be enough'. nice review/