Hello everyone, and welcome to another issue of the Words for Worlds newsletter.

Two new pieces of non-fiction SF writing from me this month: in Interzone, a review of Agnes Gomillon’s Seed of Cain, the second book in a near-future dystopic trilogy (there’s also an interview with Gomillon that I did, in the same issue of the magazine). And in India Today, a review of Siddhartha Deb’s much-talked-about alt-history novel, The Light at the End of the World.

Also, in book news, Amazon is having one of its periodic sales, so The Horizon is available at Rs 84. So if you haven’t read it yet…

What I’m Reading/Watching

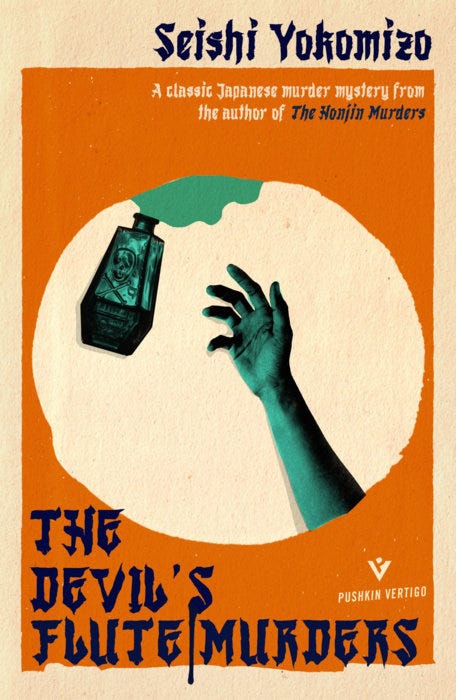

The Devil’s Flute Murders is the most recently translated crime novel from the Seishi Yokomizo, the king of the “locked room murder mystery” (and this one has - surprise, surprise! - a locked room murder!). I found The Devil’s Flute Murders very well-crafted, and actually better than Yokomizo’s more famous The Honjin Murders and The Village of Eight Graves. The building up of the suspense (and its eventual release) was particularly well-done, although the final resolution lacks a bit of the depth that you’d find in, say, a Higashino crime novel.

Season 2 of The Wheel of Time dropped at the beginning of September, and we’re now five episodes in. I think I’ve written before of my love for Season 1, and Season 2 has taken off right where S1 left off: the sets, music, and character arcs are as brilliant as they were in the previous season, but also, there is a sense of assurance to the writing that perhaps wasn’t quite there in S1: you feel that the scriptwriters are now much more sure of themselves, and the nature of their adaptation. Once again, though, I’m rather glad at how utterly I’ve memory-holed the book series (that I read in 2004-2007), so I have nothing really to compare the show to, and can enjoy it purely on the terms of this medium.

What’s Happening at Strange Horizons

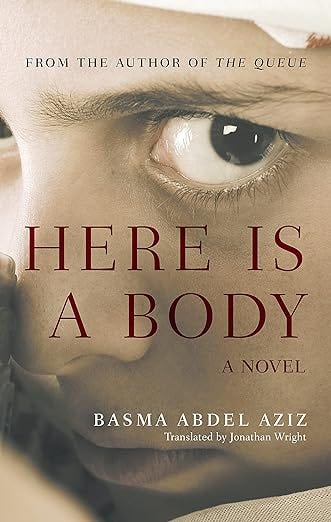

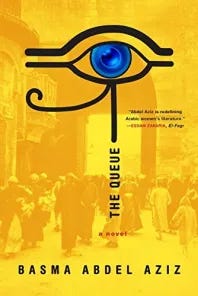

I was excited to see a review of a new novel by the Egyptian SF writer, Basma Abdel Aziz, in Strange Horizons a couple of weeks ago. In 2017, I’d read and reviewed Aziz’s first novel, The Queue. Novel #2 - Here Is A Body - appears to be in a similar vein (an SF/dystopic/weird fiction treatment of a near-future, authoritarian Egypt), and in a similar style - spare and minimalist, with “the Space” taking the place of “the Queue.” Given how good The Queue was, and given how writers often take a significant leap between their first and second books, this should be well worth a read.

The Indian Scene

A new novella by Chaitanya Murali, titled Ajakava (at the intersection of alt history, fantasy, and Indian myth) has been published by Space Wizard Science Fantasy, and is available on Amazon: one of those rare occasions when you can actually access novellas published abroad, so go for it!

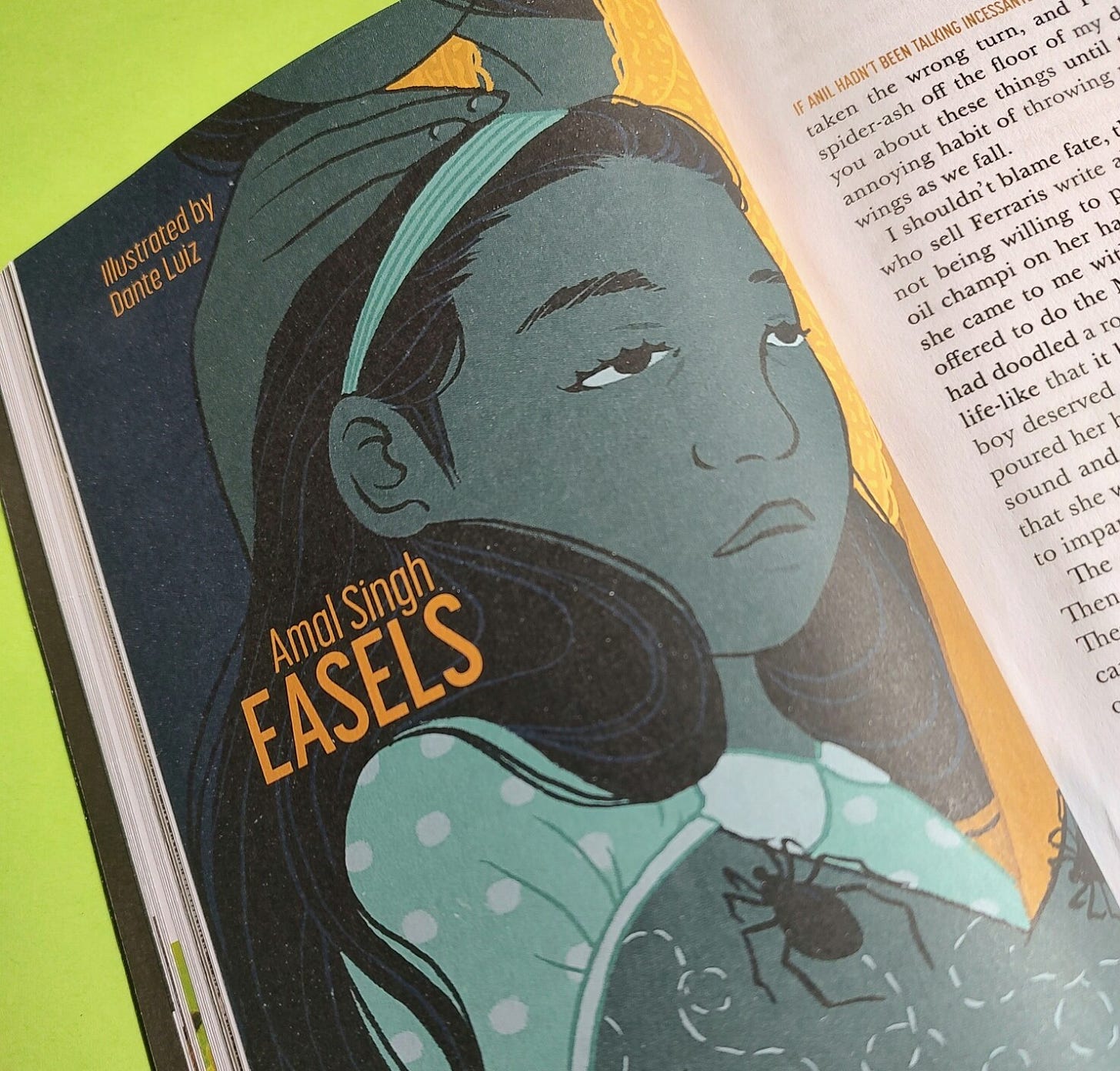

In the same issue of Interzone mentioned above, Amal Singh has a short story called “Easels.” This one will need a subscription, though.

Recommendations Corner

Since Basma Abdel Aziz’s second book is out, what better time than now to revisit The Queue? Here is a summary of the novel, and a link to the review where I put it in conversation with Omar Robert Hamilton’s The City Always Wins and Kossi Efoue’s The Shadow of Things to Come:

The Queue is set in an unnamed country, with only the names of its characters acting as geographical signposts: Tarek, Yehya, Nagy—all names redolent of the Arabic-speaking Middle-East. The country is ruled by the “Gate” (i.e., an actual, physical gate, which issues orders and directions through its proxies, and maintains discipline through a militia called the Quell Force). The Gate has assumed power after the internal disintegration of a successful popular uprising against the prior regime, referred to as “The First Storm,” and consolidated it by violently putting down a second uprising known as “The Disgraceful Events.” Now, all human life is subject to the rhythms of the Gate, which promises to open, but never does. And because nothing can be done without the sanction of the Gate, citizen-petitioners must queue before it until it opens, and their paperwork is processed. Over time, this queue—which gives Aziz’s novel its title—swells to monstrous proportions, creating its own mini-society and proliferating little economies—and continues to expand. Life is the queue, and the queue is life, with brief interludes elsewhere.