Words for Worlds - Issue LV

Hello everyone, and welcome to another issue of The Words for Worlds newsletter.

What I’m Reading/Watching

Last year, just before Apple TV began to release Season 1 of its adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, The Hindustan Times approached me to write an essay on the contemporary relevance of the novels, six+ decades after they were published.

Writing the piece (available here) gave me a chance to reacquaint myself with the series that had introduced me to science fiction, as a ten-year-old child. While there are elements of the novels that haven’t aged well (not least Asimov’s stodgy writing and his inability to write any fleshed-out female characters), at its heart, Foundation is a story about grand ambition and human hubris, the hold of the past(s) upon the future(s), and of course, all of it told on a galactic scale. All of that remains as fresh in the 2020s as it did in the 1950s, and I was curious - and excited - about the adaptation.

At the end of Season One, I was confused, but still open to see where the story was going. At the end of Season Two (it finished a couple of weeks ago), I was (and am) entirely put off: as an adaptation, I think Foundation fails at every conceivable level. But I also think it’s worth examining why and how it fails, and what that says about contemporary SFF (in particular, producers'/showrunners’/writers’ expectations about their viewers’/readers’ expectations). It’s also an interesting discussion to have, given the controversy generated by two other ongoing adaptations of very popular books: The Wheel of Time (which I am loving) and The Rings of Power (which I’m indifferent about).

So, Foundation. Let’s begin by noting that any successful adaptation of the books would need to conduct major surgery upon the source material. Some of it, I think, is good: given the hopeless gender imbalance of the original series, gender-swapping Gaal Dornick and Salvor Hardin (not to mention R. Daneel Olivaw) makes eminent good sense. Some of the timeline swaps - such as bringing the Mentallics story (which Asimov wrote into a subsequent prequel, Forward the Foundation) - into the main book-timeline is helpful, as it lets us see the birth of the Second Foundation, which is so important to the overall story. And some innovations that are nowhere to be found in the books - such as making the Galactic Emperor a three-bodied clone - create an interesting storyline in its own right, and complement the source material.

Thus, this is not a complaint about a lack of “fidelity”, per se, to the source material: if that was my gripe, I’d be hating The Wheel of Time and the many liberties they’ve taken with Robert Jordan’s ur-text.

So, where it the problem? For me, it lies in the fact that there are far too many changes whose effect is not a departure from the source text, but, in essence, it is to make the core story incoherent.

At its heart, Foundation is a story that explores the idea of historical determinism. The mathematician Hari Seldon invents a science called “psychohistory”, which posits that while the behaviour of individuals is unpredictable, the behaviour of large groups is, and can be modelled. Using Psychohistory, Seldon predicts that the reigning Galactic Empire will shortly fall, and a dark age will follow. To shorten the duration of the Dark Age, Seldon seeks - and receives - permission to start a colony on a distant planet called Terminus, with the goal of putting together a Galactic Encyclopaedia. This turns out to be a ruse: the actual purpose of establishing the colony is to create a nucleus for a Second Galactic Empire, whose rise will shorten the dark age to a mere millenium instead of the originally projected 30,000 years.

The original Foundation trilogy - Foundation, Foundation and Empire, and Second Foundation - track the evolution of Terminus through the death-throes of the Empire. At various points, the Foundation faces threats to its existence (“the Seldon Crises”), which it successfully faces down, allowing it to stick to Seldon’s predicted trajectory (“the Seldon Plan”). The remarkable thing about these crises is that once they have been surmounted, it turns out that Seldon has broadly - and correctly - predicted their nature (and resolution), by using psychohistory. Through a series of stored recordings - that Seldon decreed were to be played at specific times - the Foundation finds out that the crisis they have just faced had been predicted (as had been its resolution); of course, it is vital that these recordings are played after the crisis has been resolved.

There are three such crises that are portrayed both in the books and in the TV show. In the first crisis, the Foundation is faced with a military threat from neighbouring “barbarian” star systems, who have broken off from the Empire’s control (as tends to happen in the peripheries of a declining Empire), which it diffuses through the clever diplomacy of its mayor, Salvor Hardin, first by playing the antagonistic star systems against one another, and then by using the superior scientific technology at the disposal of the Foundation to create a “religion of scientism”, which is then used to turn the citizens of the most threatening system (Anacreon) against their rulers. This series of events are orchestrated by Hardin, but - as Seldon notes in a recording after the fact - they are historically determinate, flowing from the inevitable fracturing of the peripheries of Empire and loss of contact with the metropolis.

The TV show essentially rewrites this storyline. First, it turns Salvor Hardin into an action hero (this is particularly ironic, given that Book Hardin’s catchphrase is “violence is the last refuge of the incompetent”). Next, it dispenses completely with the scientism storyline (inexplicably shifting it forward to the next crisis), and instead resolves the crisis through a confrontation between Hardin (and others), the Anacreonian leader (“the Grand Huntress”), with the intervention of a mysterious entity called “the Vault” (originally, it seemed to correspond with the Seldon recordings from the book, but very quickly, the Vault acquires a life and powers of its own, including housing “copies” of Seldon himself). Season One ended at this point, and this is why I wrote that the ending left me confused: instead of historical forces leading to the defeat of Anacreon (the whole purpose of “psychohistory”), it turned out to be the heroic actions of Salvor Hardin, along with some good old-fashioned science fantasy (“the Vault”).

While I wasn’t quite clear about the manner in which the show resolved the first Seldon Crisis, it is in Season 2 that things became much clearer - and in a bad way. Season 2 brings together two distinct Seldon Crises from the books - involving two characters, Hober Mallow and General Bel Rios (in the book, they are separated by a few generations). Mallow is a trader/merchant-prince, who overcomes the Seldon Crisis of the day - another military threat - through a strangling economic embargo that ultimately forces the antagonistic military to stand down. This storyline, too, is entirely dispensed with in the show, with Mallow being portrayed as a “chosen one” who - after a series of close shaves - goes down with his ship in a confrontation with the Emperor. None of this storyline makes a lot of sense (the scientism thread too is thrown in here), but what is specifically jarring is the “chosen one” trope: the whole premise of psychohistory is that structural forces will always overcome individual action; the very idea of a “chosen one” is at odds with the fundamental premise of the book and the show: Hober Mallow is the individual who acts and exists, but psychohistory tells us that it might be any individual in his position, but the outcome (“the Plan”) would remain the same. What is even more bizarre is that at one point the show appears to acknowledge this - before going right back to the Chosen One trope.

Be that as it may, it is the Bel Rios storyline that made me want to tear my hair out. The Bel Rios story is one of the most brilliant illustrations of the workings of psychohistory in the books. Bel Rios, a general of the Empire, (rightly) perceives the Foundation to be an existential threat, and proceeds to launch a military assault against them. Bel Rios’ tactical acumen sees him win a series of victories - and then, at almost the last moment, he is recalled, tried, and executed (off-stage). The explanation is simple: at this stage in history, only the combination of a strong Emperor and a strong general could threaten the Foundation. A strong Emperor and a weak general could do nothing (militarily). A weak Emperor and a strong general would tempt said strong general to depose the Emperor and take the throne for himself. Only in the case of a strong general and a strong Emperor would the latter be forced to look outwards for conquest; but the moment that general threatened to become too strong, the Emperor would depose him before risking being deposed himself. This is the prediction of Psychohistory, and this is how it happens.

The show takes a hatchet to this storyline. It turns Bel Rios into an unwilling general, blackmailed into prosecuting a war he does not really want. And Bel Rios snaps when the Emperor orders the destruction of Termins, even while knowing that Bel Rios’ longtime partner has crash-landed on the planet after a recent military engagement. Bel Rios and the Emperor fight, ending with the Emperor being thrown out of the airlock, and the Genetic Dynasty being thrown into chaos back on Trantor.

The Bel Rios storyline highlights the core problem with the show in its starkest form: the very point of Foundation was to explore how structural forces move the arc of history. The show has ripped that up and given us your far-too-standard story of individual, heroic action being at the arc of history. In Foundation, Salvor Hardin, Hober Mallow, and Bel Rios act, but they act under the constraints of structural forces; the show makes them the masters of those forces.

There are other instances of the same problem scattered through the show, which are likely to worsen with the next season. In the second half of Foundation and Empire, Asimov introduces us to the Mule: a mutant with telepathic powers, whose appearance throws the Seldon Plan completely out of whack. The appearance of the Mule is where we are shown the limits of Psychohistory: that even at the structural level, an anomaly is possible, which cannot be predicted. In the show, Gaal Dornick - using her Mentallic powers - is able to look into the future and “see” the Mule. Once again, the entire purpose of this storyline - the appearance of the unpredictable within a predictable structure - is undone.

And then there is the time-traveling. One stand-out feature of the Foundation series is that there is no single protagonist: the story takes us through several stages of the Seldon Plan, and at each stage, introduces us to the characters faced with a particular Seldon Crisis. This structure fits with the overall philosophy of the books, and their focus on structural forces. In the show, Seldon and Dornick (and, until the end of Season 2, Salvor Hardin) are effectively able to travel through time and be present (and even intervene) in various Seldon Crises. Once again, then, it is individual action that carries the day.

I want to clarify that my issue is not with these storylines in themselves. You could well choose to produce a time-traveling, military space opera about the fall of a Galactic Empire, which would then be judged on those parameters. The problem is when you retain the core of the Foundation novels (the idea of Psychohistory), but then every single thing you do is inconsistent with that core. This is what leads to the internal incoherence of the show: you can either have Psychohistory, or you can have action-hero Salvor Hardin, chosen one Hober Mallow, and Bel Rios throwing the Emperor out of the airlock; but you can’t have both.

Which does raise the question: why? I don’t have a categorical answer, but I suspect it has to do with the trope-ification of modern SFF. While there is a lot to criticise about the original Foundation series, one thing that you have to say for it is that it is thoroughly anti-trope (and that’s why parts of it continue to remain as fresh as they do). A Galactic Empire without an Emperor (at least, not one at the forefront); space opera without too much of the operatic bits; no single protagonist, but several mini-protagonists within each section of the series; structural forces as narrative drivers rather than spectacular individual action or set-piece battles; the list goes on. And it’s remarkable how for every one of these, the series gives us a familiar trope: in the show, the Emperor is front and centre (and notably, the largest face on the promo photo above); there are space battles and planet-destroying weapons; and individual heroes changing the course of history through heroic action.

And the only real rationale I can glean for this is that the show-runners simply didn’t trust the audience to engage with the more challenging aspects of Foundation. They decided to serve up chicken soup-esque, familiar fare, keeping the audience firmly in their comfort zone. So they gave us the bones of Foundation - Hari Seldon, psychohistory, and the declining history - and upon that they built the most trope-y narrative you could ask for, doing away in the process with anything that would bring us into unfamiliar territory; and in doing so, they have told a story that is fundamentally incoherent, summed up by the time-traveling, deity-esque figure of Hari Seldon, who has become a deus ex machina personification of pyschohistory itself.

That is disappointing as far as the show is concerned, but I think it’s even more disappointing as a commentary on the state of mainstream SF as it stands today.

What’s Happening at Strange Horizons

Folks interested in the more global aspects of SF will find intriguing this review of Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny, by Fernanda Coutinho Teixeira. And this is one of the best closing lines I’ve read: “In a walk through Bora Chung’s tapestry of nightmares, fear is the compass one can’t help but follow.”

The most recent issue has one of my favourite poets, R.B. Lemberg, with “Firebird, Stormbird.” There’s also a new issue of the Critical Friends podcast, discussing the link between reviewing and critical practice.

The Indian Scene

There is a cornucopia of riches this week, starting with the formal publication of Tashan Mehta’s Mad Sisters of Esi, which I have mentioned before. Mad Sisters of Esi is Tashan’s second novel, after the thoroughly enjoyable The Liar’s Weave (2017). Mad Sisters of Esi is what you’d get if you painted over a Ferrante novel with the brush of magical realism. I’m not going to say much more, other than note - yet again - the quality of liquid prose in Tashan’s writing that always makes me extremely jealous. Get this one!

Congratulations also to Amal Singh for a new short story in Clarkesworld, “Rafi.” This one has Amal’s characteristic combination of the interpersonal slice-of-life intermingled with a cosmic background, topped off with a touch of weird. Give it a read!

Recommendations Corner

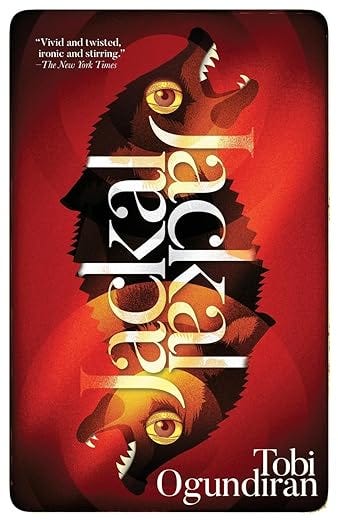

I recently read Jackal, Jackal, a collection of weird/horror short stories by Tobi Ogundiran. It reminded me a bit of Dare Sagun Falowo’s Caged Ocean Dub, which I reviewed earlier: there is a sense of defamiliarisation about these stories, which begin with familiar, known themes, but twist them in the eeriest of ways, leaving the reader thoroughly disoriented. There’s also, of course, cultural reference points that one is not entirely familiar with, given the euro/anglocentricism of cultural production in general. I think what writers like Falowo and Ogundiran do quite skilfully is that they use that sense of displacement (a slightly different canon of gods, a slightly different kind of relationship to the spirit world) to accentuate the sense of the weird in their stories. Recommended!

Thanks for sparing me the harrowing experience of watching S2, I had trouble watching S1. Completly agree on your diagnosis of SFF mainstream trope-ification. Predictability wins in an industry where predictable profitable productions are at a premium. This might explain why the structural forces of history of "psychohistory" (and possibly it's historical materialist core?) gets displaced by a relapse into 'great man' 19th c theory of history. Possibly that is why for this Apple+ adaptation the Foundation feels more like Galt's Gulch, less Asimovian and more Randyan.

I just finished S2 of foundation as well (against my volition) and agree with your analysis. I heard an account that writing rooms in hollywood are in disarray- the smaller number of senior/experienced writers who used to maintain cohesion and keep the young writers ideas under control apparently all retired early during the covid lockdowns, and have been driven out by ongoing labour disputes. To me it felt like a story written by a committee (or maybe chatGPT) like so many modern scripts. Surely the problem cannot be a matter of money when millions are spent on these projects. Why has hollywood strangled the core of its creative ecosystem?