Hello, and welcome to the first Monday of the month - and, well, the year!

I’ve done a review of my 2023 reading on my book blog, here. Lots of SF, most of which I’ve discussed in previous issues of this newsletter, but lots of other stuff as well.

This 2024 curtain-raiser issue of the newsletter will follow a slightly different format from the usual: there’s an SFF conversation that’s been going on the past few days that I want to discuss. Normal programming will resume from next fortnight: the “What I’m Reading,” “The Indian Scene,” “What’s Happening at Strange Horizons,” and “Recommendations Corner” will all be back, as normal.

One of the features of keeping up with the genre industry is that every fortnight, you have no choice but to witness an utterly absurd - and borderline infantile - set of exchanges on the internet. Earlier this month, it was an author setting up sock-puppet accounts to give low ratings to their rivals’ books on Goodreads (!). The entire discourse was reminiscent of high school. Over the last two days, it has been this tweet, by an account called “Afropessimism Apologist”:

White people writing fantasy is so interesting to me because you could imagine ANYTHING and your worlds still have rape, incest, hierarchies, pillaging, pilfering, apparatuses of social control, land theft, taxes and abuse.

Last I looked, this tweet has had 929 replies, and 2.3K quote-tweets. A majority of those are mocking the OP.

I try to avoid twitter main character syndrome like the plague, but I’ve found this particular discourse quite interesting in what it says about perceptions about the genre, and - by extension - about the state of the genre. Let me start by saying that the tweet is clumsily worded. The themes that the OP have flagged are hardly exclusive to white fantasy writers, and nor are they the sole preserve of whiteness, as understood in the racial sense. The fact that the centre of publishing power in contemporary SFF is located in the US and the UK is not quite reducible to simply “white people writing fantasy.” The difference in nuance matters.

That apart, a lot of the discourse “dunking” on the OP essentially says that what they are advocating for is dull conflict-less narratives, utopias where nothing happens. Fantasy, on the other hand, draws from life, and must have the stuff of life in it, warts and all.

The issue with this response is the conflation between conflict as a driver of narrative, and conflict born out of the exact same hierarchies and power structures that are present in the real world. OP’s tweet is essentially challenging fantasy writers by saying, if you have a chance to build a world from scratch, why would you choose to write into it our inherited hierarchies and power structures?

As a challenge, this makes eminent good sense. When I write a queer-normative world, for example, I do it because when I have the freedom to build my own world, why would I hardwire homophobia into it? Our own histories have plenty of examples of queer-normative societies, so this is not even “utopian” in any sense. And if I don’t have to burden my characters with homophobia as a driver of narrative conflict, I can create - and interrogate - far more imaginative and interesting bases of conflict. Replicating homophobia, or patriarchy, or other similar and familiar forms of social control, is simply boring, after a point.

Incidentally, “Afropessimism Apologist” is not the first person to have made this point. In one of her most famous - and most quoted - speeches, Ursula Le Guin (pictured above) said exactly this, when she called upon SF writers to imagine alternatives to capitalism:

“We live in capitalism,” said Le Guin, “Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings.” It’s up to authors, she explains in the video below, to spark the imagination of their readers and to help them envision alternatives to how we live.

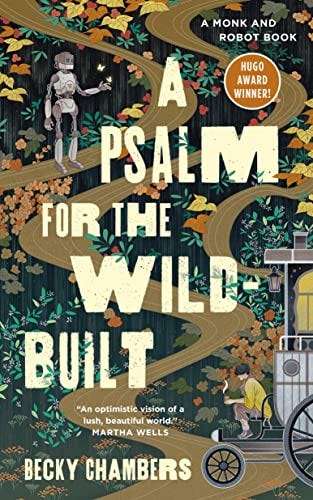

There are, in fact, SF writers who do just that. Becky Chambers’ Monk and Robot series, for example, does not use any of “rape, incest, hierarchies, pillaging, pilfering, apparatuses of social control, land theft, taxes and abuse” as drivers of narrative conflict. That doesn’t mean conflict doesn’t exist, or that Chambers’ world is a characterless void. Human beings who live in a post-scarcity, post-capitalist society will have other conflicts to contend with; the whole point of SF - as ULG told us - was to imagine what those might be.

I suspect that if you make a Venn diagram of folks dunking on “Afropessimism Apologist” and folks who swear by ULG, you’ll get two overlapping circles. Le Guin has become a bit of a Martin Luther King Jr-type figure in modern SF: deified by all, and in the process, stripped of the radicalism that made her who she was. A harmless, non-challenging deity.

I think it’s also an indicator of how so much contemporary SFF has a veneer of radicalism, but at its core, is pretty status-quoist and conservative. If challenging SF writers - whose very shtick is world-building - without rape, incest, or land theft (for example) can meet with such righteous outrage, then it speaks to a kind of collective, stunted imagination that can only think of interesting narratives being ones based on our ugliest instincts as a species.

It probably also explains why, a decade after ULG’s call to SFF writers to “imagine alternatives to the way we live,” so few have actually taken up that call. I suspect the vast majority who did found their pitches languishing somewhere at the bottom of literary agents’ query piles!